How dust storms in the world's largest desert form: revelations from a new satellite data set

Hundreds of millions of tons of dust are blown off the Sahara desert each year. This dust interferes with the climate system and is capable of both cooling and heating the atmosphere depending on its height, size, shape and colour. It also interacts with cloud formation and weather systems like tropical cyclones. On longer timescales, dust fertilizes oceans and increases the rate at which oceans take carbon out of the atmosphere. Being able to represent the location and quantity of dust in models is really important as these are the tools we use to make weather forecasts and climate projections.

The trouble with the Sahara is that we don't have a good idea what precise systems create the dust and where these systems occur most frequently. The desert is vast and largely uninhabited with very few observations made from the surface.

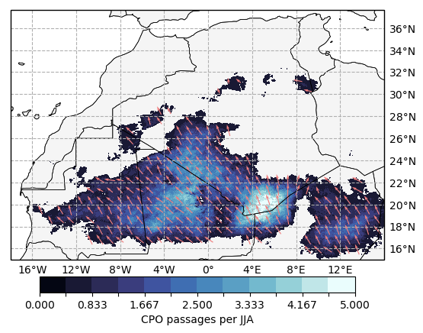

A new study from the African Climate Research group uses satellite observations to map out the occurrence of these dust storms in the Sahara for the first time. The study shows the importance of outflows from thunderstorms creating intense, cold surface winds called haboobs which cause dust storms lasting for many hours and covering hundreds of kilometers. Satellites can only measure radiation, so the key breakthrough with this study is an algorithm that detects dust produced by the intense downdrafts of thunderstorms and then tracks that dust at 15 minute intervals across the desert surface.

Maps of haboob occurrence frequency (see Figure 1) highlight a hotspot in the central Sahara which intensifies in late summer. A puzzle follows from this - what role does this hotspot have in the yearly dust budget, given that existing observations suggest dust emission peaks much earlier in the monsoon season? Evidence accumulated in the paper suggests dust sources further south in the Sahel may be more responsive to haboobs. What follows is a complex picture of Saharan dust sources and their activity in relation to seasonal winds.

The study's lead author, Thomas Caton Harrison, said: "Gust fronts due to storm downdrafts are not unique to the Sahara - they have an important role to play in sustaining intense storm systems across the tropics. They are also a significant aviation hazard. However, it's possible to observe them directly in the Sahara as they leave a plume of fine erodible material from the desert surface in their wake. This gives them a unique signature in infrared satellite imagery."

June 2020 saw one of the largest Atlantic dust plume of the last 50 years, impacting air quality thousands of kilometres away. To predict how these massive Saharan plumes may respond to climate change, however, a knowledge of processes at source is needed. As our understanding of haboobs improves, it may soon be possible to incorporate them explicitly into models used to estimate fluxes of Saharan dust from year to year and into the future.

The School of Geography and the Environment has a long standing interest in desert dust which started with the work of Prof. Andrew Goudie and Dr Nick Middleton in the 1980s. The Fennec project in 2011 and 2012 saw 200 hours of aircraft flights over the Sahara in the core of summer as well as the deployment of 30 tons of equipment in the remote Algerian Sahara to measure the dust at particular locations. The satellite-based work of Thomas Caton Harrison has provided crucial insights which were not possible from ground-based campaigns with limited sampling times.

Further information

- Caton Harrison, T., Washington, R. and Engelsteadter, S. (2020) Satellite‐Derived Characteristics of Saharan Cold Pool Outflows During Boreal Summer. JGR Atmospheres, 126(3): e2020JD033387.

How dust storms in the world's largest desert form: revelations from a new satellite data set

Hundreds of millions of tons of dust are blown off the Sahara desert each year. This dust interferes with the climate system and is capable of both cooling and heating the atmosphere depending on its height, size, shape and colour. It also interacts with cloud formation and weather systems like tropical cyclones. Being able to represent the location and quantity of dust in models is really important as these are the tools we use to make weather forecasts and climate projections.