Not a Zero-Waste of time! Interview with Professor Anna Lora-Wainwright

In brief

What does the future of zero-waste living look like in urban China? This interview with Professor Anna Lora-Wainwright explains the many forms that everyday environmentalist activism can take, and also explores the role of the individual and the state in zero-waste living.

Overview

What does the future of zero-waste living look like in urban China? This interview with Professor Anna Lora-Wainwright explains the many forms that everyday environmentalist activism can take, and also explores the role of the individual and the state in zero-waste living.

In April 2024, Professor Anna Lora-Wainwright was awarded a British Academy Small Grant along with Dr Thomas Johnson from The University of Sheffield for their project, “Zero-Waste Living in Urban China.” The project draws on ethnographic fieldwork and interviews in Hangzhou, online research, and interviews with campaigners involved in China’s Zero-Waste Alliance. It explores tensions and synergies between individual practices of zero-waste living, civil society initiatives to reduce waste, and the Chinese state’s promotion of environmental sustainability through its “ecological civilisation” and “circular economy” narratives.

The project questions the binary between low-profile acts of “everyday environmentalism” and the highly visible forms of environmental collective action that tend to generate public attention. In doing so, it provides a more nuanced understanding of human agency, subjectivity, and ethics. This approach sheds light on the multiple outcomes and meanings that these environmental movements embody and manifest—ranging from perpetuating inequality and justifying state inaction, to creating space for ethical practices and political possibilities—which are not captured well by existing approaches. The project has its roots in previous work on waste incineration and anti-incineration movements in China.

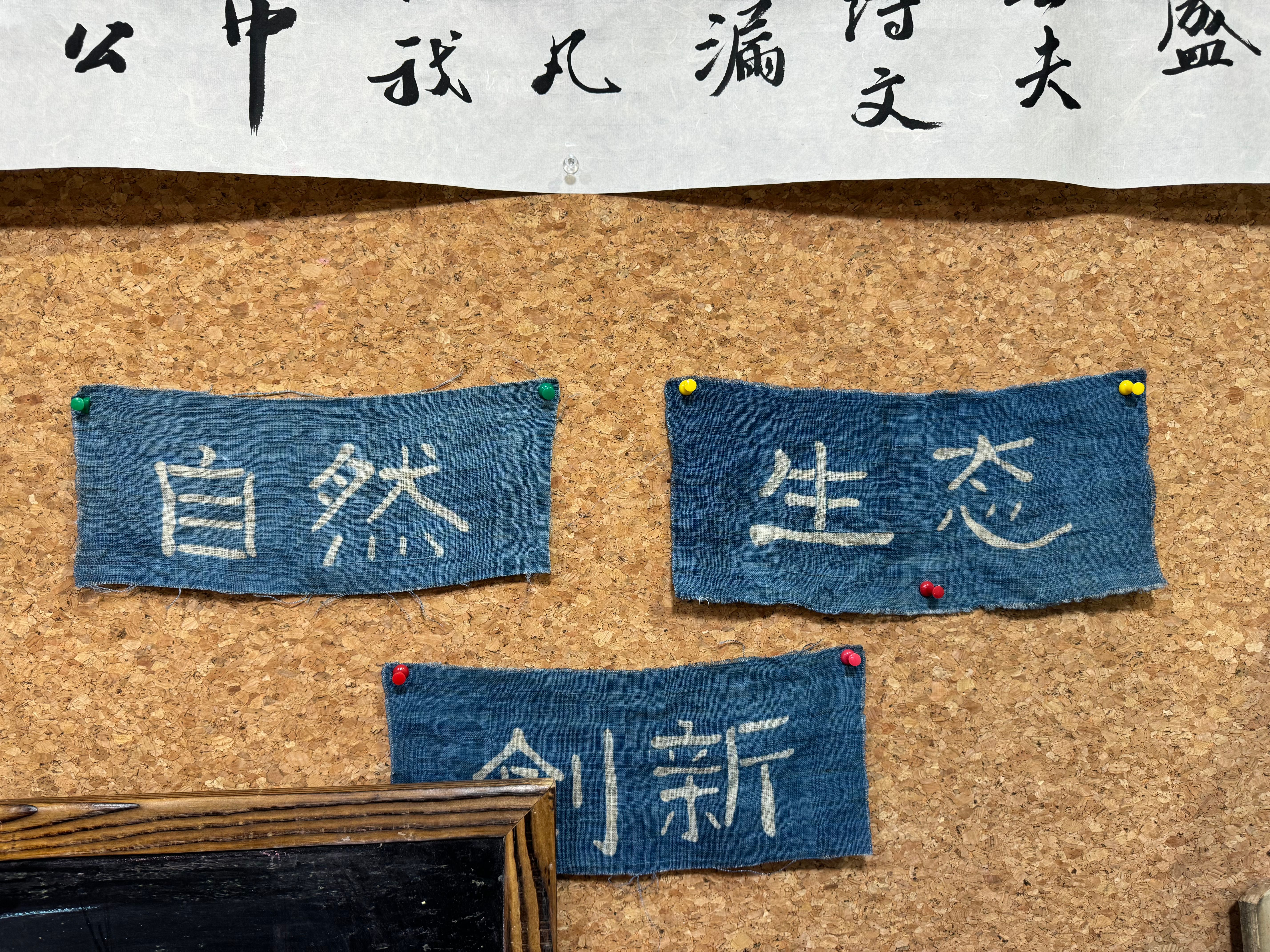

Photo: Katherine Yuet Wong

Can you tell me a bit more about the background of the project and the context of zero-waste living in urban China?

The problem of waste won’t be solved by individuals – household waste is a drop in the ocean compared to the bigger problem of construction waste, industrial waste and so on, but we are interested in seeing what individuals are trying to do as part of this bigger picture. There are many ‘opportunity gaps’ in households for practices and actions that can contribute to the zero-waste effort.

China has urbanised really quickly in the past two-to-three decades, and with urbanisation, waste typically increases. So, the stage and the mode of development that China is going through now makes waste management a really important issue. The Chinese government has recognised this urgency and is actively addressing it, primarily through promoting a "circular economy" which focuses on efficient industrial waste management.

"The problem of waste won’t be solved by individuals...but we are interested in seeing what individuals are trying to do as part of this bigger picture."

Can you tell me a bit more about how the Zero-Waste Living in Urban China project came to be?

Ten years ago, I started working on how Chinese citizens have responded to incineration with my colleagues Thomas Johnson and Jixia Lu. Over time, the project evolved, and we started to explore the introduction of waste recycling in rural areas. This project presented some challenges and was put on hold during the COVID-19 pandemic, but Tom and I continued to be interested in working on waste together. We decided that focusing on something that was taking place in the space of the household rather than through contentious protest would be more feasible and also valuable. We also share a profound concern – planetary concern – with the growth in waste streams and the need to do something about it. In essence, the project is a confluence of civil society and academic motivations. It aims to illuminate and explore individual efforts towards waste reduction within the broader context of China's urbanisation and waste management challenges.

What stage of the project are you currently at?

The project started in April 2024 and will last for two years. We currently have a PhD student, Katherine Yuet Wong, stationed in Hangzhou who has begun collecting data. Katherine has started doing some participant observation in a bulk shop (a shop where people go with containers to buy things in bulk or refill containers) and is taking part in zero-waste initiatives organised by Professor Qiu. Over the next few months, we'll combine this data with interviews of zero-waste activists across China and mini case studies of specific families to gain a comprehensive picture of how some Chinese citizens in urban China strive to live a zero-waste life. The research methodology consists of a combination of fieldwork, interviews, documentary research, and online research.

Photo: Katherine Yuet Wong

Photo: Katherine Yuet Wong

Is there a reason why you chose Hangzhou?

Yes. Firstly, Hangzhou is one of China’s ‘first tier’ cities. It is big, relatively wealthy, and generates a large quantity of waste, all of which make it a good field site. Secondly, it’s a city where the government has actively implemented pilot programmes to deal with waste. It makes sense as a site because a lot of attention has already been given to waste by the local government. There are also some really interesting civil society initiatives that are taking place concerning zero-waste. For example, there are online and offline groups facilitating exchange and second-hand trading, reflecting a strong community spirit around sustainability. Overall, Hangzhou's combination of government commitment, community engagement, and a large urban population provides a rich environment to study zero-waste practices.

What are you aiming to do with the project?

It’s always most valuable to look at people’s lives and practices from the bottom up. So, instead of just looking at description, documentary, accounts, news, we want to observe what people actually do in their lives as part of a commitment to be less wasteful. This also links to our interest in forms of agency. I'm interested in looking at how agency can be found in less visible spaces as part of a theoretical contribution to the discipline. Instead of focusing on the more striking images you see on the screen as a form of protest, we want to focus on, for example, a parent who goes to a shop with a with a plastic box to do their shopping, or people who exchange second hand goods because they don't want to create a bigger landfill problem. From a political science point of view, this doesn’t count as political activism or agency as much as more contentious actions, but I think it should. I think it's important that we pay attention to those smaller ways of participating.

Photo: Katerine Yuet Wong

Photo: Katerine Yuet Wong

Can you tell me a bit more about the distinction between everyday environmentalism and contentious collective action?

The distinction is often made starker than it is in reality. To me, there isn’t so much of a black and white divide, but shades in between. If you think of it from the point of view of the people involved, it might be that the same person is doing certain things in their home, and this creates motivation or inspiration to do things outside of the home, or vice versa. Everyday environmentalism and contentious collective action are connected and that’s partly what we are trying to show in the project.

This choice is also motivated by the fact we work in China, where increasingly working on contentious topics is off the menu. For the sake of my own safety, the safety of collaborators and the safety of the participants in the research, I think it’s a more ethical path to do research on something that is less politically visible, less contentious politically, but still interesting from the point of view of understanding social movements and forms of participation.

What do you expect the project results will show you?

I expect a lot of diversity. I predict that in some cases, following the principles of ‘zero-waste living’ is relatively straightforward, and in others it might be more difficult, with tensions emerging in families. An example of this might be children wanting sweets and their mother saying ‘no’ because they’re using up plastic.

I’m hoping that data can highlight how these sorts of difficulties are negotiated by people, which will help us understand some problems that may be faced in actually living up to ideals of being less wasteful and being more sustainable in our livelihoods.

Photo: Katherine Yuet Wong

Photo: Katherine Yuet Wong

What do you think the future of zero-waste living looks like in urban China?

The future of zero-waste living in China is also likely to be quite diverse. We expect continued government intervention in waste management, potentially scaling up existing efforts on both production and consumption sides. This could unlock unforeseen opportunities for public participation, such as innovative solutions for recycling or filling gaps in current waste reduction strategies.

Generally, there is strong state support for environmental protection in China, or what the Party-state calls ‘ecological civilisation’. This creates quite fertile and safe ground for bottom-up initiatives because they're effectively contributing to a state effort. It’s not remotely what we started out looking at: people protesting incineration. Incineration was what the state had been pushing for as a way of dealing with waste. If you’re opposing incineration, you’re opposing the state. Whereas, by following the principles of zero-waste living, you’re helping the state achieve its goals.

So, do you think that efforts towards zero-waste living in China will be a harmonious between the state and individuals?

Mostly, but they might not always meet in the middle. There may be things that the state does that won’t be met with much enthusiasm or interest from the population, or vice versa. For example, one of my previous students, Loretta Ieng-Tak Lou found some brilliant examples of resistance to consumerism through her research on “green living” in Hong Kong, such as people going to McDonald’s and eating other people’s leftovers to reduce waste. I can’t see the state being in favour of that, they’d probably brand it as unhygienic, despite there being an ethical element to the individuals doing it. However, I don’t think there will be immediate tensions. Just general off-shoots that sprout in different directions that don’t quite join up.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Many thanks to Professor Anna Lora-Wainwright!

In brief

What does the future of zero-waste living look like in urban China? This interview with Professor Anna Lora-Wainwright explains the many forms that everyday environmentalist activism can take, and also explores the role of the individual and the state in zero-waste living.