Aissa Discovers All Rhodes Lead to Oxford

In brief

Aissa Dearing, student writer, and alumna of Oriel College, examines whether statues distort the memory and legacy of those commemorated and how places are experienced through the eyes of a geographer. She is a current DPhil in the School of Geography and the Environment.

Overview

Aissa Dearing, student writer, and alumna of Oriel College, examines whether statues distort the memory and legacy of those commemorated and how places are experienced through the eyes of a geographer. She is a current DPhil in the School of Geography and the Environment.

In my college, there were reminders of him everywhere. It was more than just the tallest statue on the High Street, crowning Oriel College -- his name remained on the stained-glass windows of the College hall; outside my window there was a plaque on King Edward's Street with an inscription praising his 'great services rendered… to his country' and the prestigious global scholarship that continues to bear his name. For some of my fellow students at Oriel College, his legacy, and ultimately, Britain's colonial legacy, is a source of pride that should be celebrated: many of my peers believed that this legacy jump-started industrialization and uniquely positioned Britain to become a world power. Yet others, especially those who belong to marginalized backgrounds and have connections to countries with colonial histories, understand that these statues are not mere artifacts of the past but an emotional and contested aspect of everyday life at the University of Oxford, a reminder of the oppressive systems that still fester today.

No matter how one may view Cecil Rhodes, one thing is clear: the Rhodes Statue and commemorative plaques that decorate Oriel change how people feel in these spaces, who has ownership in these places, and whose histories are worth remembering. It is the highest statue on the public high street of the city – a special kind of reminder to the people of Oxford. A central tension emerges. Are we misremembering the past by removing the statue or continuing to commemorate Rhodes by keeping it?

Oriel's official position on the Rhodes statue is to retain and explain, a form of counter memorialization, -- not to remove or damage the statue but to create a signpost recognizing the controversy around keeping the statue in place. Though Oriel’s Governing Body resolved to remove the statue in 2020 and later commissioned an independent inquiry into the matter for greater contextualization of the issue, the Governing Body ultimately decided that removing the statue (and plaque) was an inappropriate use of charitable funds. The legal blowback that the College would face to remove the statue and plaque would cost hundreds of thousands of pounds to mitigate. Instead, the College rationalized that it made more sense to use these funds to provide scholarships for Black Academic Futures and fund research endeavours with the British Zimbabwe Research Society. While the redirection of funding for those who wish to study at Oriel, especially those from vulnerable backgrounds, is critical, any study undertaken at Oriel is still conducted under the eye of Rhodes. Symbolism, especially to prospective applicants and the residents of Oxford, matters.

But what is the point of a statue? What do they represent, and why are they kept? Who builds them, and for whom? Like other historical monuments of leaders, the Cecil Rhodes Statue sets history in stone. We cannot deny that statues are intended to be commemorative and celebratory. They do not invite dialogue of the complexity of these historical leaders into mainstream conversation. As Gary Younge writes in essay Why Every Single Statue Should Come Down: "This statue obsession mistakes adulation for history, history for heritage, and heritage for memory […] it attempts to set our understanding of what has happened beyond interpretation, investigation, or critique."

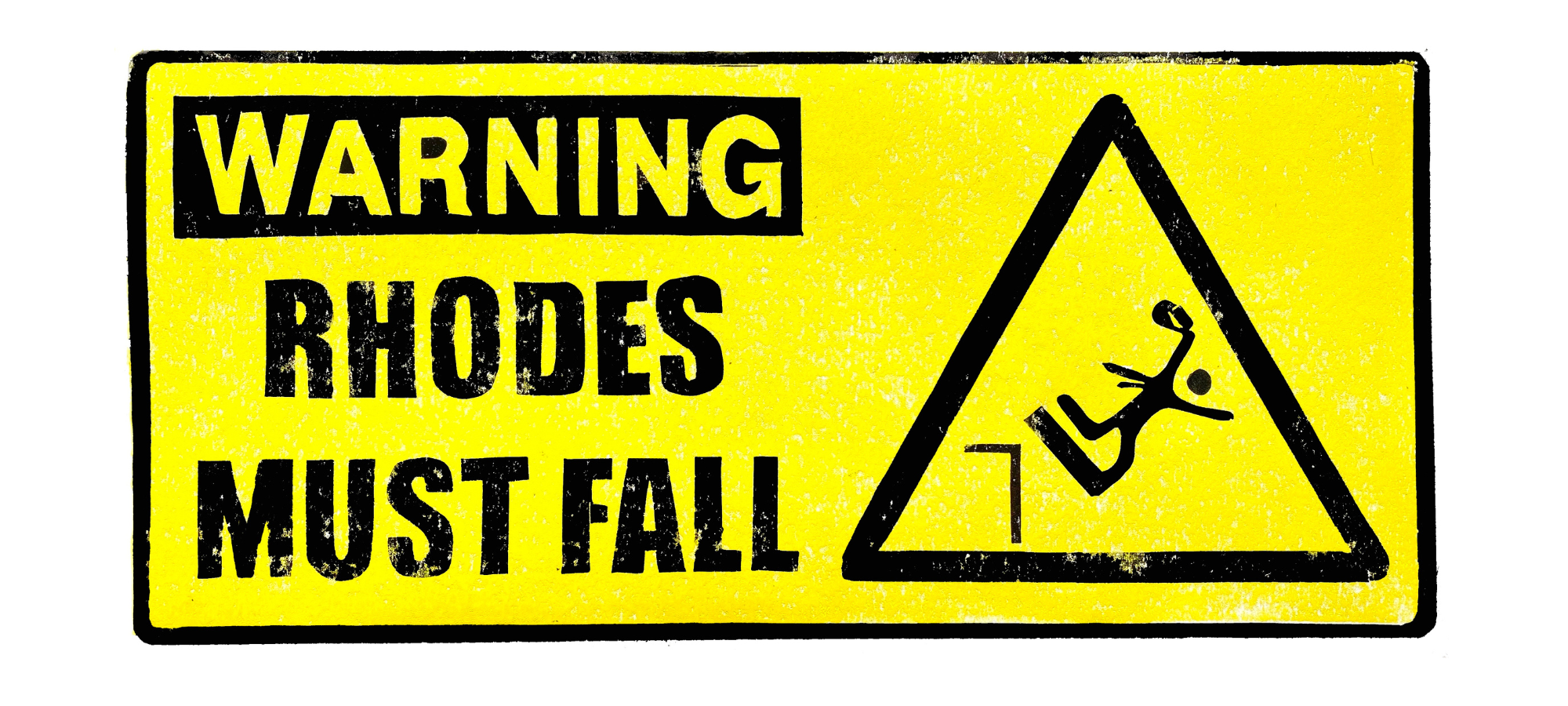

It was not the statue itself but the Rhodes Must Fall movement 100 years later that led to the modern movement around the reappraisal of Rhodes and his colonial legacy. Beginning in 2015 with Universities across South Africa, it made its way across the Atlantic to Oxford's High Street. As a representative from Oxford's Rhodes Must Fall movement, who wishes to remain anonymous said: "Statues and symbols are a means through which communities express their values." As values and interpretations of historical events naturally change over time, does it make sense to continue glorifying historical figures immutably? History, like geography, is a living discipline -- as our understanding of the past becomes greater with further discovery, our thoughts on identity, systems, and society change. It is no longer about judging history through a historical lens; it's about ensuring that as we recall historical events and their legacies, we do so in a reflective and productive way.

Nigel Biggar, a theologian at Oxford and author of Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, writes that if history was contextualized correctly, we would understand British involvement in slavery as "nothing out of the ordinary" and that violence against Indigenous people in nation-building projects is "essential" as is the "deterrence of others through fear." He calls for a moral reconsideration of colonialism -- arguing that we should not judge historical action with a modern lens. Even if the genocide of Indigenous Americans and Trans-Atlantic slavery were universally viewed as acceptable at the time (which it was not: British abolitionists as early as the 1780s have been documented advocating against the Trans-Atlantic slave trade), Oxford's High Street is not a museum where a proper contextualization of history could occur. Even for his time, Cecil Rhodes was widely criticized – backlash took place as the statue was erected. As we remember history, we must ensure we do so in a way that appreciates the complexity of the time period, allowing our public spaces to have the flexibility to reflect the values we ascribe to now.

Uncomfortable Oxford, one of the leading organizations that has worked to reconcile geography and history, works on several public engagement research projects that seek to reshape the accessibility of decolonial discourse. On an Oxford and Empire Tour with Uncomfortable Oxford, I found that discussions are encouraged among tour participants, allowing us to engage with the physical space, our emotions, and each other. In my tour group, we talked about the symbolism of statues and how simply removing Rhodes does not erase his legacy of oppression. Still, symbols are powerful. Statues, or even the lack thereof, are talking points. This discussion around Rhodes would still have occurred had the plinth been empty. It is critical to decolonize not only institutional structures -- but also physical spaces. Ambitions beyond removing statues must be supported to truly decolonize space and place.

As geographers, historians, and environmentalists at Oxford, we have a critical role in understanding how coloniality, or the ongoing legacy of colonialism, manifests across space and temporalities. The discipline of geography is not unfamiliar with systems of oppression; it is born out of the 'discovery' of what has been deemed 'empty lands' and has helped to justify the genocide and erasure of Indigenous peoples around the world. As Professor Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography at the School of Geography and Environment (SoGE) at the University of Oxford, and Sally Tomlinson write in Rule Britannia: Brexit and the End of Empire: "The purpose of geography was to produce colonial officers… to know about the empire before going out and serving in it.”

Within SoGE, there have been efforts to reconcile this past well before the onset of the Rhodes Must Fall movement– by integrating decolonial thought into the curriculum and inviting greater diversity into the student and faculty bodies. Decolonizing, or the profound challenge to the historical and current iterations of colonialism experienced centering land reform and Indigenous sovereignty, demands a bold and audacious reckoning with injustice to make space for other ways of being in the present. By working to redirect the University’s material resources to communities that have been harmed the most by colonialism and dismantling forms of coloniality in the University and beyond, we can begin to foster a decolonial world.

It's relatively easy (though important) to rename a lecture theatre or remove a statue, but much harder to make space for alternative ways of knowing, being, and understanding at the University of Oxford. Though these are small strides towards true diversity and SoGE has much more work to do, such actions signal to broader society that justice-oriented transformations are not only important but required.

I remember when I sat in my room in Oriel College, facing the Cecil Rhodes plaque on King Edward's Street. I didn't choose to come to Oriel. The scholarship that I was fortunate enough to receive matched me with Oriel, with no consultation regarding how this College's legacy and current struggles with justice would impact me as a student. It feels like Oriel has constantly granted Rhodes protections and excuses at the expense of what I needed to feel welcome and make this my own community. The statue, among other symbols and actions, reminds me that this institution was never meant for people like me. My existence at Oriel College and beyond is a form of protest. How am I to make a home in a place where I constantly have to defend my right to have my history unignored, subverted, and misrepresented?

In August 2023, Oriel College's Provost, Lord Neil Mendoza, was appointed as the Chair of Historic England, a statutory public body that advises the British government on affairs of the historic environment, including statues and plaques. Under a Labour government, there will likely not be the same legal ramifications facing Oriel if the College pursued taking the statue down – rendering the argument of ‘improper use of charitable funds’ void. Perhaps in this position, Chair Mendoza will use his influence to advocate for the same level of protection for Oriel students and beyond by removing the plaque and the statue.

Rhodes never rose, and so must fall, and will fall. They warn that once you start taking statues down and changing the names of schools and theaters, you will have to reappraise it all. Where does it end? In a conversation with Professor Dorling, he noted that just because there is no end in sight doesn't mean the necessary work of reappraisal should not start. The people of Oxford and the University of Oxford community deserve to move freely about a space that uplifts all.

Resources on Rhodes

- Protests took place as statue was erected

- Oriel College on Rhodes

- Rhodes Must Fall

- Gary Younge, Why Every Single Statue Should Come Down

- Nigel Biggar, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning

- Danny Dorling, Rule Britannia: Brexit and the End of Empire

- Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) at the School of Geography and the Environment (SoGE)

The School of Geography and the Environment’s Student Writing Team

Aissa Dearing (they/she) is a former Environmental Change and Management (MSc) student from Durham, North Carolina, USA. Her research interests lie at the nexus of political theory, sustainable development, food systems transformation, and greenhouse gas emissions reductions. Aissa has a breadth of multi-sector experience, most notably working in the Biden-Harris White House, philanthropy, Durham-based non-profits, climate journalism, and environmental justice policy development. She will continue her research this year as a DPhil in Geography and the Environment with a Clarendon Scholarship.

In brief

Aissa Dearing, student writer, and alumna of Oriel College, examines whether statues distort the memory and legacy of those commemorated and how places are experienced through the eyes of a geographer. She is a current DPhil in the School of Geography and the Environment.